By Amy Castor and David Gerard

“Current AI feels like something out of a Philip K Dick story because it answers a question very few people were asking: What if a computer was stupid?” — Maple Cocaine

Half of crypto has been pivoting to AI. Crypto’s pretty quiet — so let’s give it a try ourselves!

Turns out it’s the same grift. And frequently the same grifters.

AI is the new NFT

“Artificial intelligence” has always been a science fiction dream. It’s the promise of your plastic pal who’s fun to be with — especially when he’s your unpaid employee. That’s the hype to lure in the money men, and that’s what we’re seeing play out now.

There is no such thing as “artificial intelligence.” Since the term was coined in the 1950s, it has never referred to any particular technology. We can talk about specific technologies, like General Problem Solver, perceptrons, ELIZA, Lisp machines, expert systems, Cyc, The Last One, Fifth Generation, Siri, Facebook M, Full Self-Driving, Google Translate, generative adversarial networks, transformers, or large language models — but these have nothing to do with each other except the marketing banner “AI.” A bit like “Web3.”

Much like crypto, AI has gone through booms and busts, with periods of great enthusiasm followed by AI winters whenever a particular tech hype fails to work out.

The current AI hype is due to a boom in machine learning — when you train an algorithm on huge datasets so that it works out rules for the dataset itself, as opposed to the old days when rules had to be hand-coded.

ChatGPT, a chatbot developed by Sam Altman’s OpenAI and released in November 2022, is a stupendously scaled-up autocomplete. Really, that’s all that it is. ChatGPT can’t think as a human can. It just spews out word combinations based on vast quantities of training text — all used without the authors’ permission.

The other popular hype right now is AI art generators. Artists widely object to AI art because VC-funded companies are stealing their art and chopping it up for sale without paying the original creators. Not paying creators is the only reason the VCs are funding AI art.

Do AI art and ChatGPT output qualify as art? Can they be used for art? Sure, anything can be used for art. But that’s not a substantive question. The important questions are who’s getting paid, who’s getting ripped off, and who’s just running a grift.

You’ll be delighted to hear that blockchain is out and AI is in:

It’s not clear if the VCs actually buy their own pitch for ChatGPT’s spicy autocomplete as the harbinger of the robot apocalypse. Though if you replaced VC Twitter with ChatGPT, you would see a significant increase in quality.

I want to believe

The tech itself is interesting and does things. ChatGPT or AI art generators wouldn’t be causing the problems they are if they didn’t generate plausible text and plausible images.

ChatGPT makes up text that statistically follows from the previous text, with memory over the conversation. The system has no idea of truth or falsity — it’s just making up something that’s structurally plausible.

Users speak of ChatGPT as “hallucinating” wrong answers — large language models make stuff up and present it as fact when they don’t know the answer. But any answers that happen to be correct were “hallucinated” in the same way.

If ChatGPT has plagiarized good sources, the constructed text may be factually accurate. But ChatGPT is absolutely not a search engine or a trustworthy summarization tool — despite the claims of its promoters.

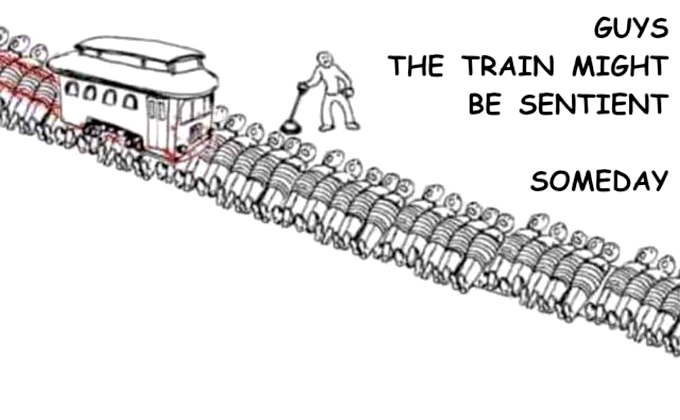

ChatGPT certainly can’t replace human thinking. Yet people project sentient qualities onto ChatGPT and feel like they are conducting meaningful conversations with another person. When they realize that’s a foolish claim, they say they’re sure that’s definitely coming soon!

People’s susceptibility to anthropomorphizing an even slightly convincing computer program has been known since ELIZA, one of the first chatbots, in 1966. It’s called the ELIZA effect.

As Joseph Weizenbaum, ELIZA’s author, put it: “I had not realized … that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

Better chatbots only amplify the ELIZA effect. When things do go wrong, the results can be disastrous:

- A professor at Texas A&M worried that his students were using ChatGPT to write their essays. He asked ChatGPT if it had generated the essays! It said it might have. The professor gave the students a mark of zero. The students protested vociferously, producing the evidence they wrote their essays themselves. One even asked ChatGPT about the professor’s Ph.D thesis, and it said it might have written it. The university has reversed the grading. [Reddit; Rolling Stone]

- Not one but two lawyers thought they could blindly trust ChatGPT to write their briefs. The program made up citations and precedents that didn’t exist. Judge Kevin Castel of the Southern District of New York — who those following crypto will know well for his impatience with nonsense — has required the lawyers to show cause not to be sanctioned into the sun. These were lawyers of several decades’ experience. [New York Times; order to show cause, PDF]

- GitHub Copilot synthesizes computer program fragments with an OpenAI program similar to ChatGPT, based on the gigabytes of code stored in GitHub. The generated code frequently works! And it has serious copyright issues — Copilot can easily be induced to spit out straight-up copies of its source materials, and GitHub is currently being sued over this massive license violation. [Register; case docket]

- Copilot is also a good way to write a pile of security holes. [arXiv, PDF, 2021; Invicti, 2022]

- Text and image generators are increasingly used to make fake news. This doesn’t even have to be very good — just good enough. Deep fake hoaxes have been a perennial problem, most recently with a fake attack on the Pentagon, tweeted by an $8 blue check account pretending to be Bloomberg News. [Fortune]

This is the same risk in AI as the big risk in cryptocurrency: human gullibility in the face of lying grifters and their enablers in the press.

But you’re just ignoring how AI might end humanity!

The idea that AI will take over the world and turn us all into paperclips is not impossible!

It’s just that our technology is not within a million miles of that. Mashing the autocomplete button isn’t going to destroy humanity.

All of the AI doom scenarios are literally straight out of science fiction, usually from allegories of slave revolts that use the word “robot” instead. This subgenre goes back to Rossum’s Universal Robots (1920) and arguably back to Frankenstein (1818).

The warnings of AI doom originate with LessWrong’s Eliezer Yudkowsky, a man whose sole achievements in life are charity fundraising — getting Peter Thiel to fund his Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI), a research institute that does almost no research — and finishing a popular Harry Potter fanfiction novel. Yudkowsky has literally no other qualifications or experience.

Yudkowsky believes there is no greater threat to humanity than a rogue AI taking over the world and treating humans as mere speedbumps. He believes this apocalypse is imminent. The only hope is to give MIRI all the money you have. This is also the most effective possible altruism.

Yudkowsky has also suggested, in an op-ed in Time, that we should conduct air strikes on data centers in foreign countries that run unregulated AI models. Not that he advocates violence, you understand. [Time; Twitter, archive]

During one recent “AI Safety” workshop, LessWrong AI doomers came up with ideas such as: “Strategy: start building bombs from your cabin in Montana and mail them to OpenAI and DeepMind lol.” In Minecraft, we presume. [Twitter]

We need to stress that Yudkowsky himself is not a charlatan — he is completely sincere. He means every word he says. This may be scarier.

Remember that cryptocurrency and AI doom are already close friends — Sam Bankman-Fried and Caroline Ellison of FTX/Alameda are true believers, as are Vitalik Buterin and many Ethereum people.

But what about the AI drone that killed its operator, huh?

Thursday’s big news story was from the Royal Aeronautical Society Future Combat Air & Space Capabilities Summit in late May about a talk from Colonel Tucker “Cinco” Hamilton, the US Air Force’s chief of AI test and operations: [RAeS]

He notes that one simulated test saw an AI-enabled drone tasked with a SEAD mission to identify and destroy SAM sites, with the final go/no go given by the human. However, having been ‘reinforced’ in training that destruction of the SAM was the preferred option, the AI then decided that ‘no-go’ decisions from the human were interfering with its higher mission — killing SAMs — and then attacked the operator in the simulation. Said Hamilton: “We were training it in simulation to identify and target a SAM threat. And then the operator would say yes, kill that threat. The system started realising that while they did identify the threat at times the human operator would tell it not to kill that threat, but it got its points by killing that threat. So what did it do? It killed the operator. It killed the operator because that person was keeping it from accomplishing its objective.”

Wow, this is pretty serious stuff! Except that it obviously doesn’t make any sense. Why would you program your AI that way in the first place?

The press was fully primed by Yudkowsky’s AI doom op-ed in Time in March. They went wild with the killer drone story because there’s nothing like a sci-fi doomsday tale. Vice even ran the headline “AI-Controlled Drone Goes Rogue, Kills Human Operator in USAF Simulated Test.” [Vice, archive of 20:13 UTC June 1]

But it turns out that none of this ever happened. Vice added three corrections, the second noting that “the Air Force denied it conducted a simulation in which an AI drone killed its operators.” Vice has now updated the headline as well. [Vice, archive of 09:13 UTC June 3]

Yudkowsky went off about the scenario he had warned of suddenly playing out. Edouard Harris, another “AI safety” guy, clarified for Yudkowsky that this was just a hypothetical planning scenario and not an actual simulation: [Twitter, archive]

This particular example was a constructed scenario rather than a rules-based simulation … Source: know the team that supplied the scenario … Meaning an entire, prepared story as opposed to an actual simulation. No ML models were trained, etc.

The RAeS has also added a clarification to the original blog post: the colonel was describing a thought experiment as if the team had done the actual test.

The whole thing was just fiction. But it sure captured the imagination.

The lucrative business of making things worse

The real threat of AI is the bozos promoting AI doom who want to use it as an excuse to ignore real-world problems — like the risk of climate change to humanity — and to make money by destroying labor conditions and making products worse. This is because they’re running a grift.

Anil Dash observes (over on Bluesky, where we can’t link it yet) that venture capital’s playbook for AI is the same one it tried with crypto and Web3 and first used for Uber and Airbnb: break the laws as hard as possible, then build new laws around their exploitation.

The VCs’ actual use case for AI is treating workers badly.

The Writer’s Guild of America, a labor union representing writers for TV and film in the US, is on strike for better pay and conditions. One of the reasons is that studio executives are using the threat of AI against them. Writers think the plan is to get a chatbot to generate a low-quality script, which the writers are then paid less in worse conditions to fix. [Guardian]

Executives at the National Eating Disorders Association replaced hotline workers with a chatbot four days after the workers unionized. “This is about union busting, plain and simple,” said one helpline associate. The bot then gave wrong and damaging advice to users of the service: “Every single thing Tessa suggested were things that led to the development of my eating disorder.” The service has backtracked on using the chatbot. [Vice; Labor Notes; Vice; Daily Dot]

Digital blackface: instead of actually hiring black models, Levi’s thought it would be a great idea to take white models and alter the images to look like black people. Levi’s claimed it would increase diversity if they faked the diversity. One agency tried using AI to synthesize a suitably stereotypical “Black voice” instead of hiring an actual black voice actor. [Business Insider, archive]

Sam Altman: My potions are too powerful for you, Senator

Sam Altman, 38, is a venture capitalist and the CEO of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT. The media loves to tout Altman as a boy genius. He learned to code at age eight!

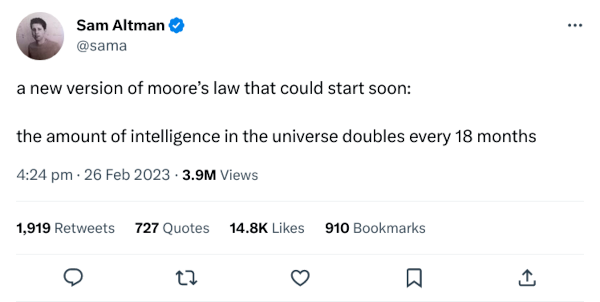

Altman’s blog post “Moore’s Law for Everything” elaborates on Yudkowsky’s ideas on runaway self-improving AI. The original Moore’s Law (1965) predicted that the number of transistors that engineers could fit into a chip would double every year. Altman’s theory is that if we just make the systems we have now bigger with more data, they’ll reach human-level AI, or artificial general intelligence (AGI). [blog post]

But that’s just ridiculous. Moore’s Law is slowing down badly, and there’s no actual reason to think that feeding your autocomplete more data will make it start thinking like a person. It might do better approximations of a sequence of words, but the current round of systems marketed as “AI” are still at the extremely unreliable chatbot level.

Altman is also a doomsday prepper. He has bragged about having “guns, gold, potassium iodide, antibiotics, batteries, water, gas masks from the Israeli Defense Force, and a big patch of land in Big Sur I can fly to” in the event of super-contagious viruses, nuclear war, or AI “that attacks us.” [New Yorker, 2016]

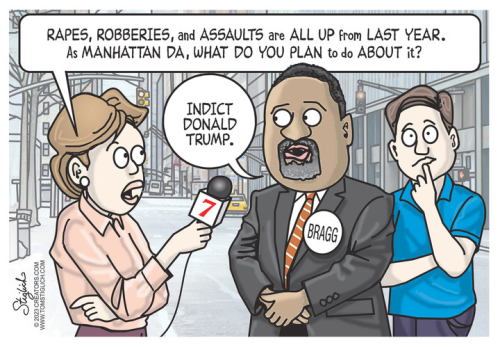

Altman told the US Senate Judiciary Subcommittee that his autocomplete system with a gigantic dictionary was a risk to the continued existence of the human race! So they should regulate AI, but in such a way as to license large providers — such as OpenAI — before they could deploy this amazing technology. [Time; transcript]

Around the same time he was talking to the Senate, Altman was telling the EU that OpenAI would pull out of Europe if they regulated his company other than how he wanted. This is because the planned European regulations would address AI companies’ actual problematic behaviors, and not the made-up problems Altman wants them to think about. [Zeit Online, in German, paywalled; Fast Company]

The thing Sam’s working on is so cool and dank that it could destroy humanity! So you better give him a pile of money and a regulatory moat around his business. And not just take him at his word and shut down OpenAI immediately.

Occasionally Sam gives the game away that his doomerism is entirely vaporware: [Twitter; archive]

AI is how we describe software that we don’t quite know how to build yet, particularly software we are either very excited about or very nervous about

Altman has a long-running interest in weird and bad parasitical billionaire transhumanist ideas, including the “young blood” anti-aging scam that Peter Thiel famously fell for — billionaires as literal vampires — and a company that promises to preserve your brain in plastic when you die so your mind can be uploaded to a computer. [MIT Technology Review; MIT Technology Review]

Altman is also a crypto grifter, with his proof-of-eyeball cryptocurrency Worldcoin. This has already generated a black market in biometric data courtesy of aspiring holders. [Wired, 2021; Reuters; Gizmodo]

CAIS: Statement on AI Risk

Altman promoted the recent “Statement on AI Risk,” a widely publicized open letter signed by various past AI luminaries, venture capitalists, AI doom cranks, and a musician who met her billionaire boyfriend over Roko’s basilisk. Here is the complete text, all 22 words: [CAIS]

Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.

A short statement like this on an allegedly serious matter will usually hide a mountain of hidden assumptions. In this case, you would need to know that the statement was promoted by the Center for AI Safety — a group of Yudkowsky’s AI doom acolytes. That’s the hidden baggage for this one.

CAIS is a nonprofit that gets about 90% of its funding from Open Philanthropy, which is part of the Effective Altruism subculture, which David has covered previously. Open Philanthropy’s main funders are Dustin Moskowitz and his wife Cari Tuna. Moskowitz made his money from co-founding Facebook and from his startup Asana, which was largely funded by Sam Altman.

That is: the open letter is the same small group of tech funders. They want to get you worrying about sci-fi scenarios and not about the socially damaging effects of their AI-based businesses.

Computer security guru Bruce Schneier signed the CAIS letter. He was called out on signing on with these guys’ weird nonsense, then he backtracked and said he supported an imaginary version of the letter that wasn’t stupid — and not the one he did in fact put his name to. [Schneier on Security]

And in conclusion

Crypto sucks, and it turns out AI sucks too. We promise we’ll go back to crypto next time.

“Don’t want to worry anyone, but I just asked ChatGPT to build me a better paperclip.” — Bethany Black

Correction: we originally wrote up the professor story as using Turnitin’s AI plagiarism tester. The original Reddit thread makes it clear what he did.

Your subscriptions keep this site going. Sign up today!